Történelmünk

A Rend története Magyarországon, a kezdetektől 1919-ig

A kezdettől Mohácsig

A Szent János Lovagrend, később Máltai Lovagrend, magyarországi fénykora a XII–XVII. századig terjedt.

A Rend alapítása után egy évtized múlt csak el, midőn a Rend magyar kapcsolatainak első okirati emléke felbukkant. Egy Petronilla nevű nemes hölgy 1135-ben Jeruzsálemben magyar ispotályt rendezett be, amelynek adásvételi szerződést a magyarokon kívül Raymond de Puy, a Szent János Rend nagymestere is aláírta. 1147-ben átvonultak Magyarországon a Szent János Lovagrend és a Templomosok németföldi és nyugateurópai lovagjai, a második keresztesháborúba vonulás alkalmából. II. András király egyik vezetője volt az ötödik (1217-1221) keresztes hadjáratnak, amelynek során felvették a Rendbe, mint donátus (laikus, adakozó rendtag). (Korán hazatért, 1218-ban, így nem vett részt a szerencsétlen egyiptomi hadjáratban.)

A magyar zarándokok szentföldi megjelenésével és az első korai keresztesháborúkkal csaknem egyidőben létesültek hazánkban jánosrendi ispotályok, rendházak és templomok. A jánoslovagok 1138-ban Székesfehérvárott telepedtek le, ahol 1156-ban rendházuk épült. II. Géza özvegye, Eufrozina királyné pedig több mint ötven birtokot adományozott nekik

A Rend magyarországi történetét abban a vonatkozásban kell megérteni, hogy egyrészt határterülete volt a kereszténységnek, másrészt a Szentföldi szárazföldi útvonalon volt. Így viszonylag sokkal kevesebb lovagot küldött a Szentföldre, mint más európai területek, hanem itthon tartotta ereje nagy hányadát, hogy az átutazók gondját viselje, azokat védje, és a helyi pogány veszélyek ellen hadakozzon. Ugyanakkor birtokai jövedelméből hozzájárult a szentföldi hadviseléshez, és elöljárói részt vettek a nagy rendi megbeszélésekben.

A Rend fontos szerepeket töltött be főleg az ország nyugati felén, többek közt rendészeti és közjegyzői feladatokat. A jánoslovagok egyik magyarországi érdekessége, hogy hiteles helyként (királyi közjegyzőként) működtek: például az Aranybulla hét példánya közül egyet ők őriztek. A Szent János Lovagrend magyar tartományának jelentőségét tükrözi, hogy II. Endre király és utána minden Árpád-házi király és herceg a Rend donátusa volt.

Helyt álltak az ország védelmében, például a tatárjárás idején, amikor a muhi csatában erősen részt vettek, és a menekülő királyt ők kísérték Dalmáciába. Egy kivétellel: 1247-ben IV. Bélától hűbérbe kapták a szörényi bánságot, az Oltig terjedő területeket és Kunország egy részét, azzal az elvárással, hogy kiváló tapasztalataikat hasznosítva vesznek részt a védelmi rendszer kiépítésében, de ők ezt nem teljesítették, és a területről rövid idő után kivonultak – nem tudjuk biztosan, hogy miért. A 14. század elején Magyarországon már több, mint 30 rendházuk állt; ezek többsége a Dunántúlon és a Drávától délre. Vezető rendházaik az esztergomi, a székesfehérvári és a budafelhévízi voltak.

Az Árpád dinasztia utáni trónviszályban a Rend a pápa utasítása dacára sokáig tartózkodott az Anjou trónkövetelő igényének elismerésétől (valószínűsíthetően azért, mert rendházaik többsége a más trónkövetelők, illetve a Károly Róberttel nem barátságos kiskirályok – Csák Máté és a Kőszegiek - területein állt. A döntő fordulatot az 1306-os év hozta el, amikor Károly ostrommal visszavette Esztergom várát a Kőszegiektől; ekkor egyértelműen mellé állt az esztergomi rendház, majd példáját követve a többiek is. Károly 1312-es hadjáratán már a „johannitáknak” nevezett lovagok alkották Károly (nem túl nagy) nehézlovasságának gerincét, és bátor helytállásukkal jelentős szerepet játszottak a rozgonyi győzelemben. Luxemburgi Zsigmonddal már kevésbé volt jó a viszonyuk.

A 14-ik században a templomosok beolvasztásával a rend igen megerősödött. Magyarországon nem üldözték a templomosokat, hanem a templomos rend feloszlatása után a birtokaik és lovagjaik beolvadtak a jánoslovagok közé. A XV. században a Rendnek több mint 40 háza volt, csak a Dunántúlon 20. Ezeknek részét a templomosok feloszlatása után kapták birtokba, így 1336-ban a fontos tengerparti Vrána erődjét, amely 1409-ig a magyar és szlavóniai jánoslovagok központja lett.

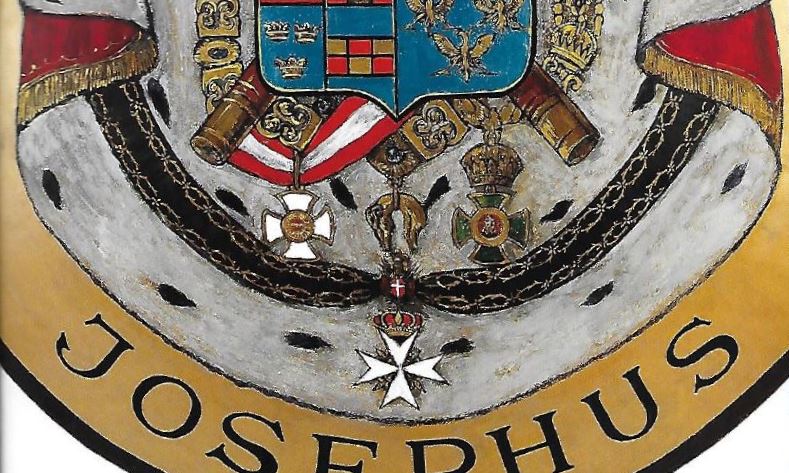

Az 1400-as években a magyar johannita lovagok kapcsolata a rodoszi központtal legyengült, hozzájárulásaikat se fizették be többé, bár 1364 és 1370 közt egy hadtestük részt vett a rend Rodosz, Ciprus és Alexandria körüli hadjáratában. Anyagi körülményeik egyre gyengültek. Vrána várát eladták Velencének, bár a "Vránai perjel" cím megmaradt. A vránai perjelt gyakorlatilag a magyar király nevezte ki, bár általában a rend jóváhagyta. Ferenc József császár még 1895-ben kinevezett egy új címzetes vránai perjelt, a zágrábi nagyprépost személyében.

A rendtagok részt vettek az egyre növekvő oszmán veszély elleni küzdelemben.

Mohácstól Trianonig

Mohács után egymás után elvesztek a dunántúli nagy konventek: Esztergom, Székesfehérvár, a magyarföldi ispotályok. Egy időre a Rend magyarországi vezetősége Sopronban talált otthonra, de ez az utolsó johannita rendház is hamar más kézre került. Ezzel a Rend magyarországi jelenléte gyakorlatilag megszűnt.

A 17-ik század elején a rend német "Langue"-ja magához csatoltatta az addig olasz nyelv alá tartozó magyar nagyperjelséget, amelynek főnöke a császár által kinevezett címzetes vránai perjel volt, kevés kötődéssel a rendhez. Három évszázad telt el úgy a magyar máltaiak történetében, ezt a „címzetes nagyperjelek” korának nevezik, hogy bár voltak magyar máltai lovagok – főleg az osztrák-cseh nagyperjelség tagjaiként - de a Rendnek önálló intézménye, szerve magyar földön nem volt. A 18-ik században voltak ugyan kísérletek a magyar nagyperjelség visszaállítására, de siker nélkül.

A 19-ik század közepén a magyar nyelvű rendtagok érdeklődéssel nézték az Itáliából érkező híreket a rend megújulásáról és a nemzeti szövetségek létesítéséről. De mint az osztrák-magyar monarchia polgárai, nem volt szabad cselekvésük. Csak a monarchia szétesése és a trianoni tragédia nyitottak új fejezetet a Rend magyarországi történalmében.

Bibliográfia:

Dr. Török József: " A Rend története hazai földön", A Magyar Máltai Lovagok Szövetségénak Emlékkönyve (2003)

Seward, Desmond: The Monks of War (Penguin Books, 1972, 1995).

Hunyadi, Zsolt (2006). Johanniták a középkori Magyarországon 1410-ig (PDF)

Thierry Heribert: A jeruzsálemi szent János máltai lovagrend magyar bibliográfiája; Fővárosi Ny., Budapest, 1941

Vajay Szabolcs: A Máltai Rend magyar lovagjai, 1530–2000. Mikes, Budapest, 2002